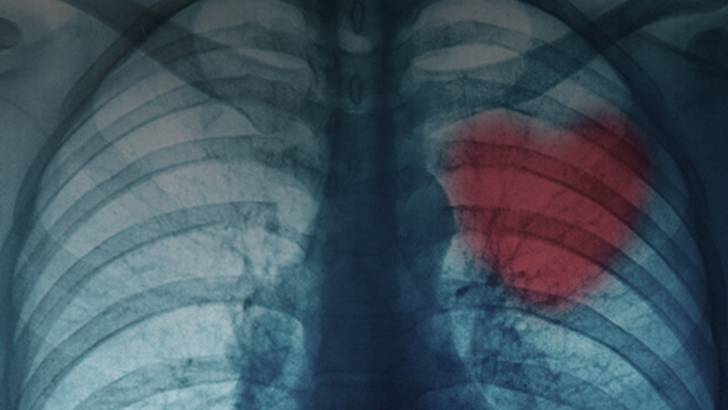

Donation of the heart after asystole leads to questions about the point at which death is irreversible. Dr. Armand Antommaria, assistant professor in the division of pediatric inpatient medicine and an adjunct assistant professor in the division of medical ethics and humanities at the University of Utah School of Medicine, discusses the ways that pediatric cardiac transplant surgery may be pushing controversial organ-retrieval strategy beyond acceptable legal, moral, and ethical boundaries. Hosted by Dr. Maurice Pickard.

ReachMD

Be part of the knowledge.™We’re glad to see you’re enjoying ReachMD…

but how about a more personalized experience?

Pediatric Heart Transplantation: Ethical Questions

Do we need a new definition of cardiac death when it involves pediatric heart transplants? Welcome to Ethics in Medicine on ReachMD XM 157, I am your host, Dr. Maurice Pickard and joining me today is Dr. Amron Antommaria, Assistant Professor in the Division of Pediatric Inpatient Medicine and Adjunct Assistant Professor in Division of Medical Ethics and Humanities at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

DR. PICKARD:

Thank you for very much for joining us Dr. Antommaria.

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

Hello, thank you for your invitation.

DR. PICKARD:

On August 14, 2008, the New England General of Medicine published an article by Dr. M. M. Russack. Interview describes 3 cases that underwent cardiac transplantation. The recipient's average 2.2 months and now survived at least 3.5 years and the donors were of the average of 3.7 days that had undergone devastating neurologic injury. Their surrogates were all in favor of transplantation and there being a donor. The controversy in this article is a reason about the period of asystole between the onset of asystole and the beginning of the transplant. The initial case was 3 minutes and the next 2 cases averaged about 1.25 minutes of asystole before they were pronounced dead. What in this article has caused such controversy?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

I think that there are 2 main issues in this article, one is whether or not its ever appropriate to transplant heart from children who are declared dead according to cardiovascular criteria and if it is ever appropriate, how long of a period of asystole or meeting the criteria for death one has to observe before declaring dead.

DR. PICKARD:

Well, do you have a definition of what is called cardiac death that we can use?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

So, in many areas this is an active area of controversy, so when donation after cardiac death processes or initially proposed, there were substantial criticism on that patients who met this criteria weren’t actually dead. Would it be worth to talk in general about what the donation after cardiac death or DCD process is?

DR. PICKARD:

Yes, I think that would be fine for many of us were not aware of it.

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

So, the donation after cardiac death process is that a patient surrogate have made the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment and it is anticipated that after this life sustaining treatment is discontinued that the patient will die within a finite period of time, typically 60 to 90 minutes and the patient's family is then approached to consent for organ donation and if they do consent, then typically the patient is taken to an operating room where they are potentially prepped and draped and cannula inserted, life-sustaining treatment is withdrawn. The family potentially says their goodbyes, death is declared, and then organ donation occurs. The initial controversy about whether or not these patients were dead centered around whether or not the cessation of cardiac and respiratory activity was irreversible.

DR. PICKARD:

This is a very good point. I mean the person becomes asystolic and there apparently has been no report of cases where the heart starts again after 60 seconds unless CPR is used, so isn't it in fact if you wait 2 minutes, isn't it irreversible, the surrogate doesn't want you to use CPR, the heart is stopped, isn't this irreversible?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

So, some people have argued that it's not irreversible because you could do CPR and restart the heart where other people would say that because the surrogate or family has decided not to use CPR, in this case that it is in fact irreversible. The general consensus has been that given the decision not to use CPR, it is irreversible and these individuals can become donors and then the question for how long you have to wait for irreversibility.

DR. PICKARD:

Do you think its enough to say that since there has been no case that the heart has started on its own after 60 seconds, that’s enough scientific evidence and data to support the irreversibility of this?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

And I think that’s part of the question. So, the database on which the 60 or 65 seconds is based is relative small. So, Davita who has the most kind of most comprehensive review of this, has an N of about 109 patients and so part of the question is, you know, with the 109 patients have bigger confidence interval, you know, how uncertain are you if the longest time we know of, was 65 if you had another 100 or 500 patients that one of us not going to go out to 70 or 75 seconds.

DR. PICKARD:

I keep coming back to the fact that we have 3 alive children and 3 deceased children where without these transplants; we certainly would have had 6 deceased children. All the ethical vector seemed to be pointing in the direction of doing this type of surgery. The surrogate is in the favor of the donor and certainly not going to survive and we get a live healthy child out of it. Are we being seduced by this or we are changing the rules in order to help our own selves work this problem through?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

And I think that is one of the really complicated issues in donation after cardiac death is that there are numbers of conflicts of interest and part of the question is whether or not we have been inappropriately pushed to increase the number of transplantable organs in order to benefit recipients and in some way harming donors.

If you are just tuning in, you are listening to ethics in medicine on ReachMD XM 157, the channel for medical professional. I am your host Dr. Maurice Pickard and joining me today is Dr. Amron Antommaria, Assistant Professor in the Division of Pediatric Inpatient Medicine at the University of Utah School of Medicine and we are talking about the controversy that exists now about short periods of asystole in order to prevent warm ischemia from taking place in pediatric cardiac transplants.

DR. PICKARD:

We know that 25% of all infants waiting for hearts, will die, and this is 10 times as many as will exist in an adult population. Should this is anyway influence us?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

I would agree that it potentially should influence us in ways to potentially identify more appropriate donors and to provides palliative care and emotional support recognizing that it may never be possible to have sufficient numbers of donors, but the question is when you kind of crossover from harming potential donors while seeking to benefit recipients.

DR. PICKARD:

I should mention that in the New England Journal article that I have referred to, there are at least 4 other articles dealing with this particular central article and one of the commentaries said that we should just focus and consent of the surrogate and the prognosis and we have to step forward that in every breakthrough in medicine, sometimes something has to be done to change our focus. In other words, I think, he almost looking at the body as an integrated system rather than a collection of organs, and therefore if we think only about consent and the prognosis, we would move in this direction, how would you respond to that?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

As a background statement, I would congratulate the New England Journal of medicine for providing a rich discussion of the issue surrounding this main paper by the group had done for children and there are number of potential alternatives outlined by the respondent. The potential alternative of the current situation, which would be potentially not recovering hearts for transplantation, and the main commentators, Reach, Dreug, and Miller all seem to find that unacceptable and Dreug and Miller do emphasize, as you have said, in obtaining valid informed consent and part of the question is, you know, how broadly are they willing to take the legitimacy of informed consent because they are in some point, willing to say that the dead donor rule, the rule that says you don’t recover organs from living persons becomes irrelevant. In the beginning of bioethics, Paul Ramsey, presented the speculative case of a parent who wanted to donate his heart to his child, and part of the question is it only hinges on consent what stops a parent who is not in the process of dying from saying I am willing to give up my heart to my child knowing that it will result in my death.

DR. PICKARD:

We see that in directed donors, people coming forward who were directed donors and often have psychiatric problems or depressive problems that have to be evaluated, and I think, one of the commentators address this, that there have to be that kind of safeguard to prevent that. Do you think, that if we change our criteria, they were in danger of losing the public trust?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

Part of the question is, whether or not, we actually need to change the criteria because the heart is restarted in another body that allows us to maintain the current criteria. If you look at the human body as an integrated system, once the donor has stopped breathing and their heart has stopped beating and a sufficient time has elapsed to prevent auto resuscitation, they are dead and that the fact that their heart can be restarted in another system, may not in fact violate the rule requiring irreversibility. So, although none of the commentators discussed it, part of the question is whether or not, what is being done actually undermines or violates the current rules including the dead donor rule.

DR. PICKARD:

Yes, because some people have come forward and said we are actually ending life by organ removal, which will be certainly going in a different direction, and which you just suggested. How to you respond to somebody who is, you know, ending life by organ removal and are being motivated by transplant service?

DR. ANTOMMARIA:

My response would be that in fact you are removing all of the organs including the heart, or the liver, or the kidneys after the patient is dead, and that transplanting the liver or the kidneys does not kill the patient. So, I think potentially it is some misunderstanding, but I agree that there is a fundamental issue of the public trust, and whether or not, there is widespread either public consensus or social understanding that what is happening is appropriate or whether there is going to be a public reaction to this which undermines public support for organ transplantation.

DR. PICKARD:

Now today, we have been discussing a new advancement certainly an attempt by the people in Denver, to move forward and to provide more donors for cardiac donation. We still haven’t answered it and there is still a tension and _______ that exists in our medical community, but certainly there are 3 babies now, 3-1/2 years old, that are alive and wouldn’t have been alive unless they had move forward.

I would like to thank our guest, Dr. Amron Antommaria who has been our guest today.

You have been listening to Ethics in Medicine on ReachMD XM 157, The Channel for Medical Professionals. For a complete program guide and pod casts visit www.reachmd.com. For comments or questions, call us toll free at 888-MD XM 157.

Thank you for listening.

This is Dr. Rick Maze with University of Reichmann at Reichmann, Virginia, and you are listening to ReachMD XM 157, The Channel for Medical Professional.

Recommended

Overview

Donation of the heart after asystole leads to questions about the point at which death is irreversible. Dr. Armand Antommaria, assistant professor in the division of pediatric inpatient medicine and an adjunct assistant professor in the division of medical ethics and humanities at the University of Utah School of Medicine, discusses the ways that pediatric cardiac transplant surgery may be pushing controversial organ-retrieval strategy beyond acceptable legal, moral, and ethical boundaries. Hosted by Dr. Maurice Pickard.

Facebook Comments